Iceland is home to 269 named glaciers, showcasing nearly every glacial type found worldwide, from massive ice caps to smaller cirque and mountain glaciers. Dominating the southeast of the island is Vatnajökull, the largest ice cap in Europe by volume, covering approximately 7,900 km², an area about three times the size of Luxembourg.

Glaciers cover around 11% of Iceland’s land area, or about 11,400 km² in total. The 13 largest glaciers (see location on map) account for nearly all of this, measuring a combined 11,181 km², highlighting how much of the country’s ice mass is concentrated in its biggest ice caps and outlet glaciers. But this iconic landscape is undergoing profound and rapid change.

Across the globe, glaciers are shrinking in response to a warming climate, and Iceland is no exception, its glaciers are among the fastest retreating in the world.

Since 1900, Icelandic glaciers have lost roughly 20% of their surface area, with almost half of that loss occurring since the year 2000.

An estimated 8.3 billion tonnes of ice have melted from Iceland's glaciers each year on average since the turn of the century, equating to an annual thinning of about one meter.

If this trend continues, many of the country’s smaller glaciers could disappear before the end of the 21st century.

A Legacy Written in Ice, and in Retreat

A Legacy Written in Ice, and in Retreat

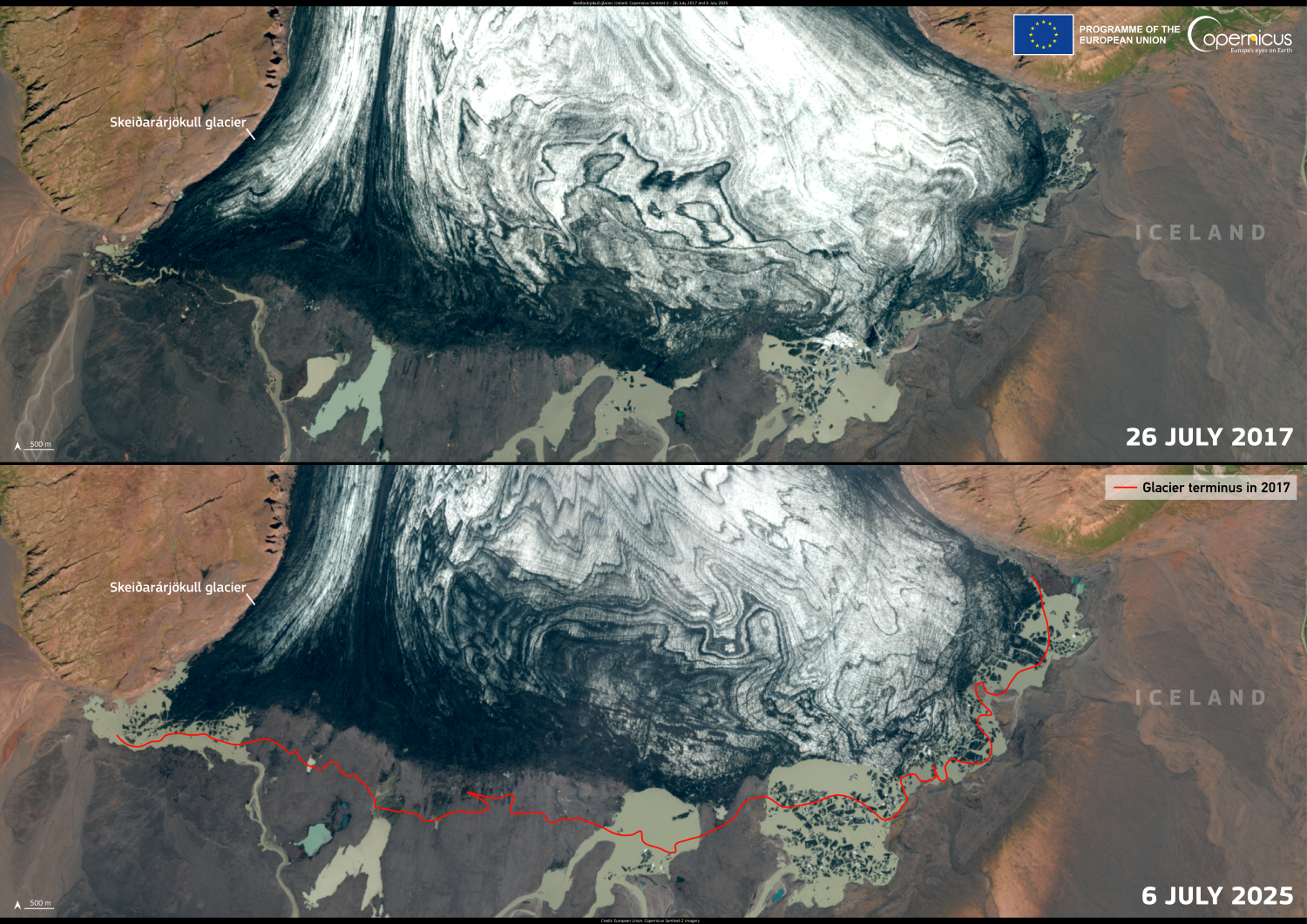

Measurements and satellite imagery confirm the accelerating melt. New Copernicus satellite images of Skeiðarárjökull, a major outlet glacier of Vatnajökull, show it has retreated by 500 to 1,000 meters on average between 2015 and 2023. According to glaciologist Þorsteinn Þorsteinsson from the Icelandic Meteorological Office, this retreat is consistent with over a century of data collected by the Icelandic Glaciological Society (see location on map).

"From 1925 to around 1950, Skeiðarárjökull retreated by as much as 1–2 kilometers. Then it advanced slightly during the 1960s to 1980s. But since 1995, the retreat has become rapid again, between 50 and 100 meters per year, sometimes more,” Þorsteinn explains. Today, Iceland’s glaciers are collectively losing around 10 billion tonnes of ice per year, with 85–90% of that loss coming from Vatnajökull and its outlet glaciers like Skeiðarárjökull, Skaftafellsjökull, Svínafellsjökull, Heinabergsjökull, and Fláajökull.

A Changing Landscape

As glaciers retreat, the Icelandic landscape is reshaped. Glacial lagoons are forming where ice has receded—such as the now-famous Jökulsárlón, but many others are emerging in less-traveled areas. Rivers change their course, land rises due to decreased ice weight (post-glacial rebound), and mountain slopes become less stable, increasing the risk of landslides and floods. These changes have implications for infrastructure planning, tourism safety, and long-term hydropower management.

Andri Gunnarsson, chairman of the Icelandic Glaciological Society, notes that heatwaves, like the one in May 2025, can trigger sudden and extreme melting. During that event, Brúarjökull thinned by a full meter in just a few days, a significant loss for that short timeframe. Andri points out that the transition from winter accumulation to summer melt is becoming sharper, especially when winter snowfall is limited.

Small Glaciers at Greater Risk

Iceland’s smaller glaciers are especially vulnerable to warming. Glaciers such as Hofsjökull East, Tindfjallajökull, and Þrándarjökull lack the volume to withstand repeated warm years. "The smaller they are, the less ice they have in reserve," Andri explains. Indeed, around 40–50 smaller glaciers in Iceland have already vanished, including Okjökull (see location on map), the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier in 2014 due to its insufficient thickness and movement.

Hydropower and the Icy Reservoir

Glacial meltwater is vital for Iceland’s renewable energy system, particularly hydropower. While the increase in meltwater due to warming might temporarily benefit energy production, it poses long-term concerns. “The big glaciers like Vatnajökull, Hofsjökull, and Langjökull are still large and currently provide increased runoff,” says Andri. “But as they shrink, this runoff will eventually decline.”

Interestingly, many of the smaller vanishing glaciers drain directly to the sea and have little influence on power production, but their disappearance signals the broader ecological shift.

Looking Ahead

Despite excellent glacier monitoring programs in Iceland, experts stress the need for global climate action. “We have a wealth of knowledge and data from institutions like the Icelandic Meteorological Office and the Institute of Earth Sciences,” says Andri. “But in the end, this is a climate issue. If we want to slow this trend, we must cut greenhouse gas emissions.”

The evidence of Iceland’s changing glaciers is visible not only in data, but also on the ground—new landscapes where ice once stood, exposed rock ridges, and lagoons slowly expanding inland. As the ice continues to retreat, the transformation of Iceland’s environment serves as both a warning and a call to action for the world.

Source: Veðurstofa Íslands, mbl.is, Copernicus